Famous comedian and writer Ricky Gervais is an outspoken atheist and a champion of rationality under the guise of science. In a popular interview, Gervais supports his disbelief in religious ideas through analogy; he makes the claim that if all human culture were erased, novel spiritual stories and ideas would emerge, dissimilar to those we are familiar with today. Conversely, he claims that all of science would reemerge just as it is today — reinstated as the objective and rational basis of reality.

This has always bothered me for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that science and religion are not opposed, but rather two sides of the same coin.1 In reading Ilya Prigogine and Isabelle Stengers’ 1978 book, ‘Order Out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue With Nature’, I have been deeply enamoured with their detailing of the evolution of science. We tend to think of science as an impenetrable and agnostic oracle — one oblivious to the trivialities of Man and his culture. Curiously, the irrevocable connection between scientific ideas, culture and philosophy is the intimately connected to the way science has come to be understood.

“It is often said that without Bach, we would not have had the “St. Matthew Passion” but that relativity would have been discovered without Einstein. Science is supposed to take a deterministic course, in contrast with the unpredictability involved in the history of the arts… When we look back at the strange history of science…, we may doubt the validity of such assertions… There are striking examples of facts that have been ignored because the cultural climate was not ready to incorporate them into a consistent scheme.”

— Prigogine & Stengers 1978

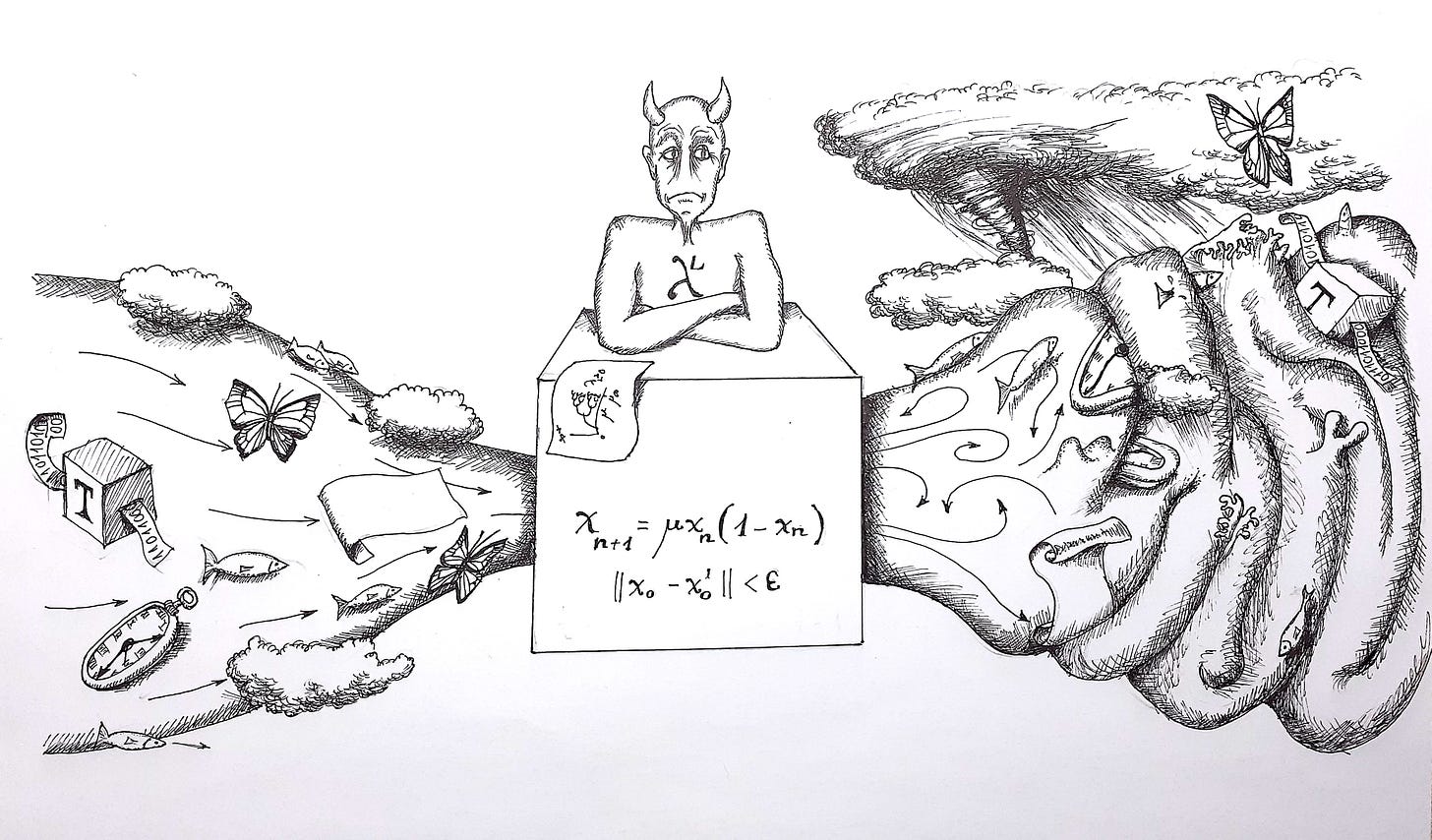

Their focus was predominantly with determinism — a view of the world that aligned with dynamicists’ hope that given enough information about the initial conditions of a system, they could not only predict the precise future of the system, but also peer infinitely deeply into its past. This opened a door to a world where intellect ruled and Man had dominion over Nature — a cultural shift towards man as God.

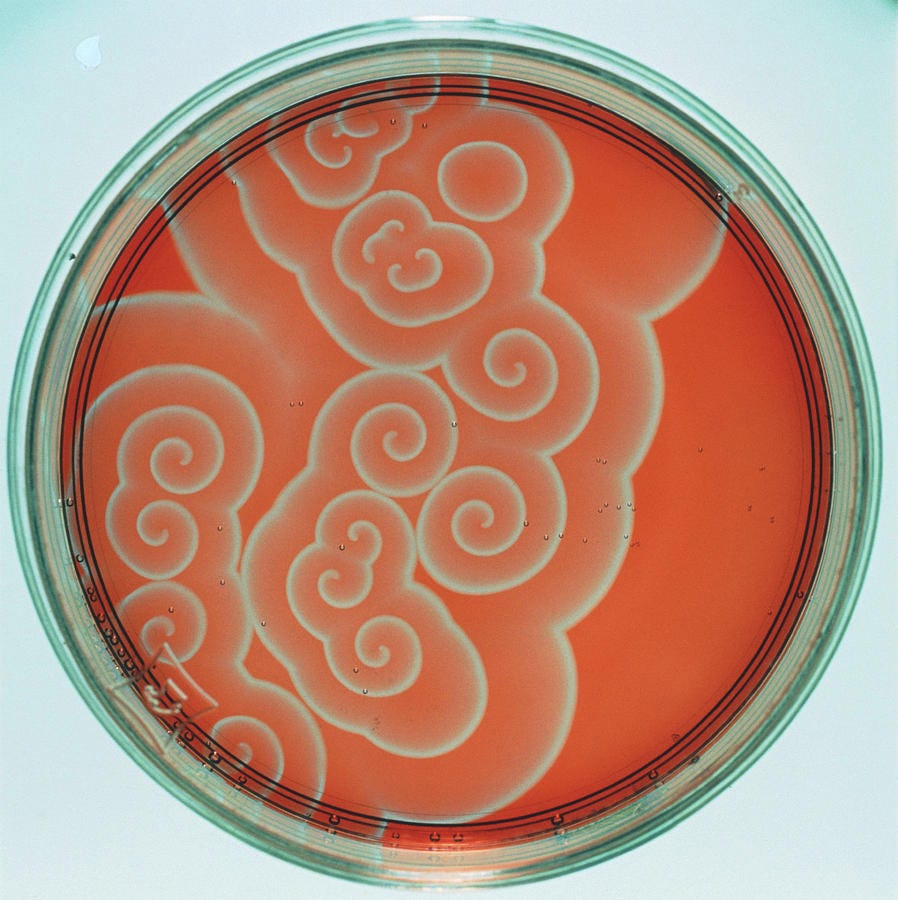

Here, our dialogue with Nature assumed a new form, one of extraction. The language of science narrowed as we sought the ability to predict and, ultimately, undermine the natural world. Here is where, gradually, big “S” Science — a collaborative, equal and open dialogue — morphed into its current small “s” iteration. This is precisely what we see in the scientific literature today, a knowledge economy of uncontextualised ‘facts’ that do little else but to serve the interests of the pharmaceutical companies. What can really be done with the knowledge that glutamate modulates white adipose tissue inflammation?2

What is most interesting to me was to see more explicitly that ‘answers’ gained through the action of our dialogue are always presented in the same language with which we ask the question.

“[I]t is true that, whether the answer is “yes” or “no,” it will be expressed in the same theoretical language as the question. However, this language, too, develops according to a complex historical process involving nature’s replies in the past and its relations with other theoretical language. In addition, new questions arise corresponding to the changing interests of each period. This sets up complex relationship between the specific rules of the scientific game—particularly the experimental method of reasoning with nature, which places the greatest constraint on the game—and a cultural network to which, sometimes unwittingly, the scientist belongs.”

— Prigogine & Stengers 1978

I have argued previously that the linear, reductionistic and anaemic language used by those like Bryan Johnson (and his team) to understand health has provided them with answers in an identically linear, reductionistic and anaemic language.3 Theirs is not a dialogue with Nature, but rather an extraction — a failure to stop and listen closely and deeply to the response.

I personally think, unlike Gervais, that in his hypothetical scenario, it would be almost certain that science as a dialogue with Nature would reemerge as a different language, one that may have taken a vastly different route, urged on by the unique cultural and philosophical ideas of the time. Perhaps this new science would be grounded in reciprocity and heterarchy, where the actions of man could not be detached from the multiplicities of relationships to which they are bound.4

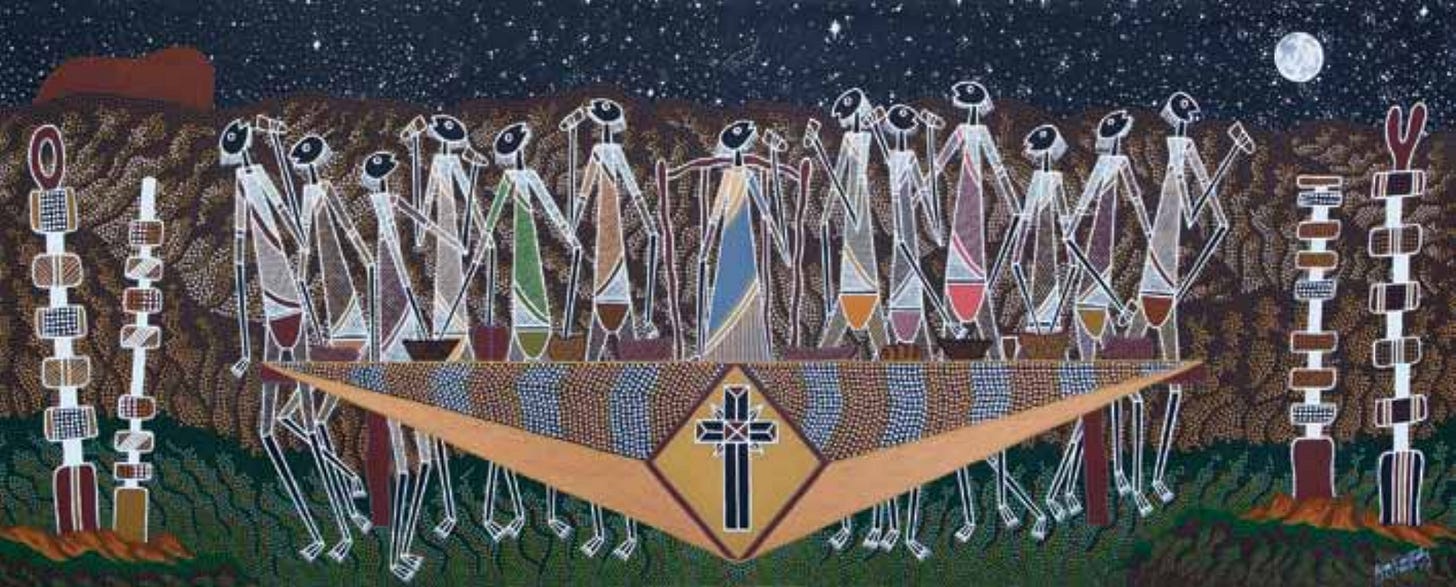

We might not even be so heretical to suggest that spiritual ideas might return in a similar form to those of our time. The spiritual stories of the world are archetypal in nature, with many of the concepts mirrored between the Judeo-Christian, ancient Egyptian, Mesapotamian and other indigenous cultures. Religious ideation appears baked into the fabric of Man — where religion is abandoned, other false idols are substituted. It does not seem too farfetched to think that similar archetypal stories could reemerge to help us understand the story of us.

All of this is to muse on the idea that what we call “science” today is a language — one that developed in a complex milieu of culture and philosophy throughout various parts of the world. This language is not objective. It is a culmination of ideas and forces that are far from rational or agnostic, yet it is parodied as the language of the Nature — our most reliable arbiter. But there exists other languages used to generate and maintain an open dialogue with Nature, like those of indigenous cultures worldwide. Such languages do not yield knowledge of chemical structures or metabolic pathways, but meaningful wisdom and insight into the habits of the natural world.

“Sometimes science is more art than science. A lot of people don’t get that.”

— Rick & Morty

There may never have been a time where questioning the language we use to generate our dialogue with Nature is more important. A realisation that Nature can only answer us in the same language with which we ask our questions is a pivotal way forward — a way beyond the knowledge economy towards one of reciprocity and wisdom.

Relevant Articles

Relevant Podcasts

Ulrike Granögger: Evidence For The Wave Genome

Andrew Marino: The Truth About a Life in Science

Dean Radin: Quantum Mechanics, Consciousness & Biology

Rupert Sheldrake has written extensively on healing the divide between science and spiritual practices. His books have been an important dialogue on this issue, as for science to regain its ability to have a dialogue with the natural world, it must first be reconciled with spiritual ideas.

I have written about this issue in a previous post titled, “Deriving Ought From Is: The empty promise of reductionistic science.”

I have called this phenomena “The Bryan Johnson Fallacy”, whereby an assumption is made that what is known is all there is to know. Here, answers can become ‘anti-useful’, where the element of truth fails to contextualise the whole.

Of course, this is not new. Science is practiced in a vastly different way in the cultural East compared to the cultural West. One must only consider the depth of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurveda or even healing traditions from indigenous cultures to realise that science can take on various guises. The idea that Western science is the most rational is indefensible. However, for us who have been brought up in such a context, it can be difficult to view science as having evolved out of ideas and cultural norms that would now be seen as ridiculous or outdated.