Electric Microbiomes

How our microbial colonies are sculpted by the flow of energy.

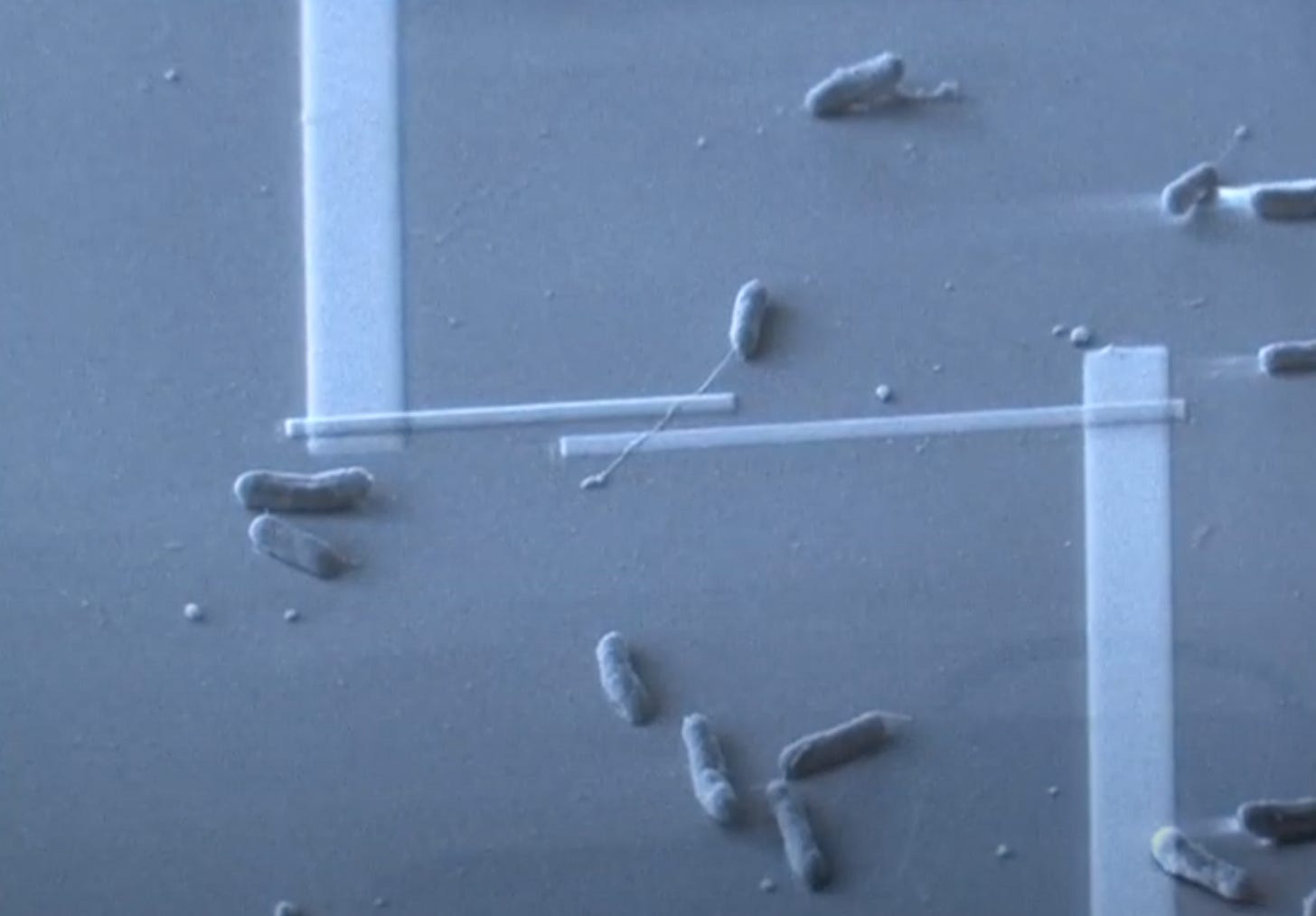

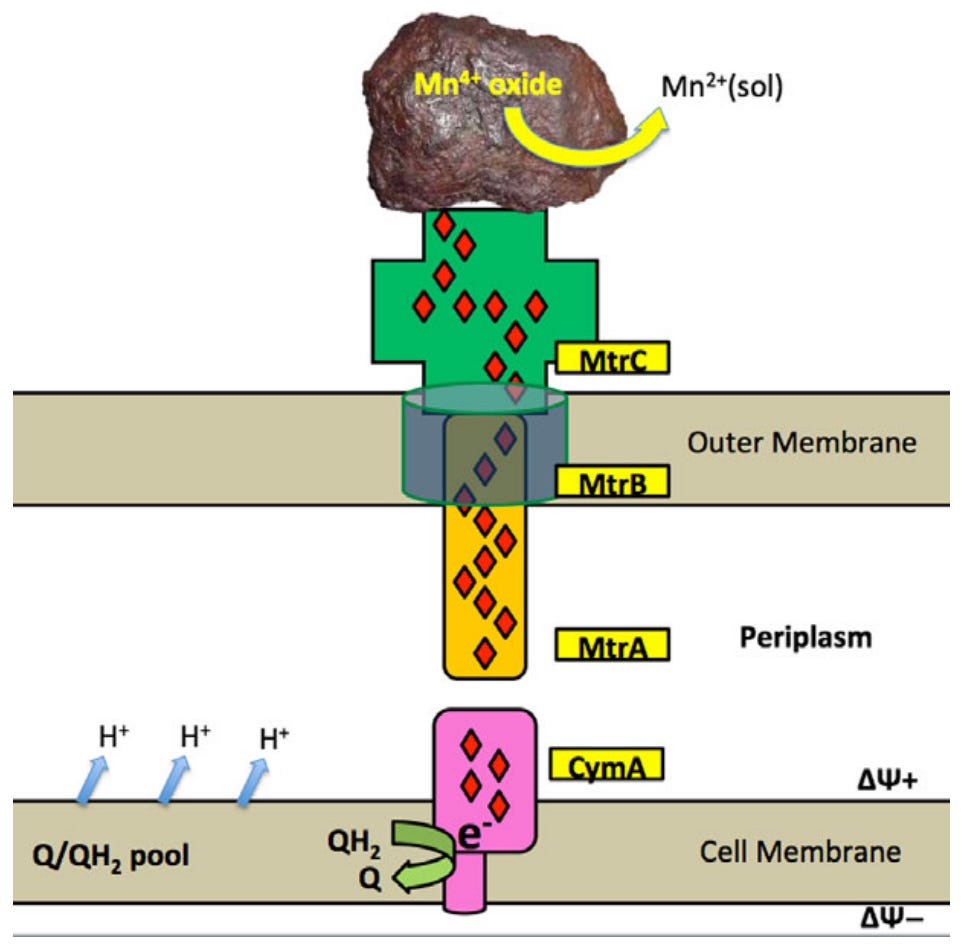

In the late 1980s, two research groups independently identified bacteria capable of living on solid metal oxides by using them as terminal electron acceptors. In effect, they “breathe” the metal oxides by using them the same way we use oxygen.1 Instead of electron transport being restricted to the internal compartment, these bacteria utilise extracellular electron transport (EET) where the terminal electron acceptors or electron donors are outside. While the electrical nature of microbes dates back to 19112, scarce attention was paid to this phenomena for the best part of a century. In 1988, Nealson and colleagues found a unique type of bacteria that used natural manganese oxide deposits to accept the electrons they use to drive energy metabolism.

Later studies by Kenneth Nealson and colleagues examined marine sediment bacteria that utilise EET to gain a deeper understanding about how cultures of these bacteria survive in varying electrical environments. Fascinatingly, some bacteria appear to be able to live solely on electricity. Rather than harvesting electrons from food and fluxing them through to a terminal acceptor, transforming energy along the way, these bacteria took up electrons directly from their surroundings to drive their energy metabolisms — no carbon source required.3 This phenomena has allowed for more reliable isolation of electrochemically active microbes by culturing under specific cathodic current flows — a feat that is otherwise extremely difficult to accomplish.4

“[B]acteria are capable of production and/or consumption of electricity, and that these processes are involved with many redox activities.”

— Nealson, 2017

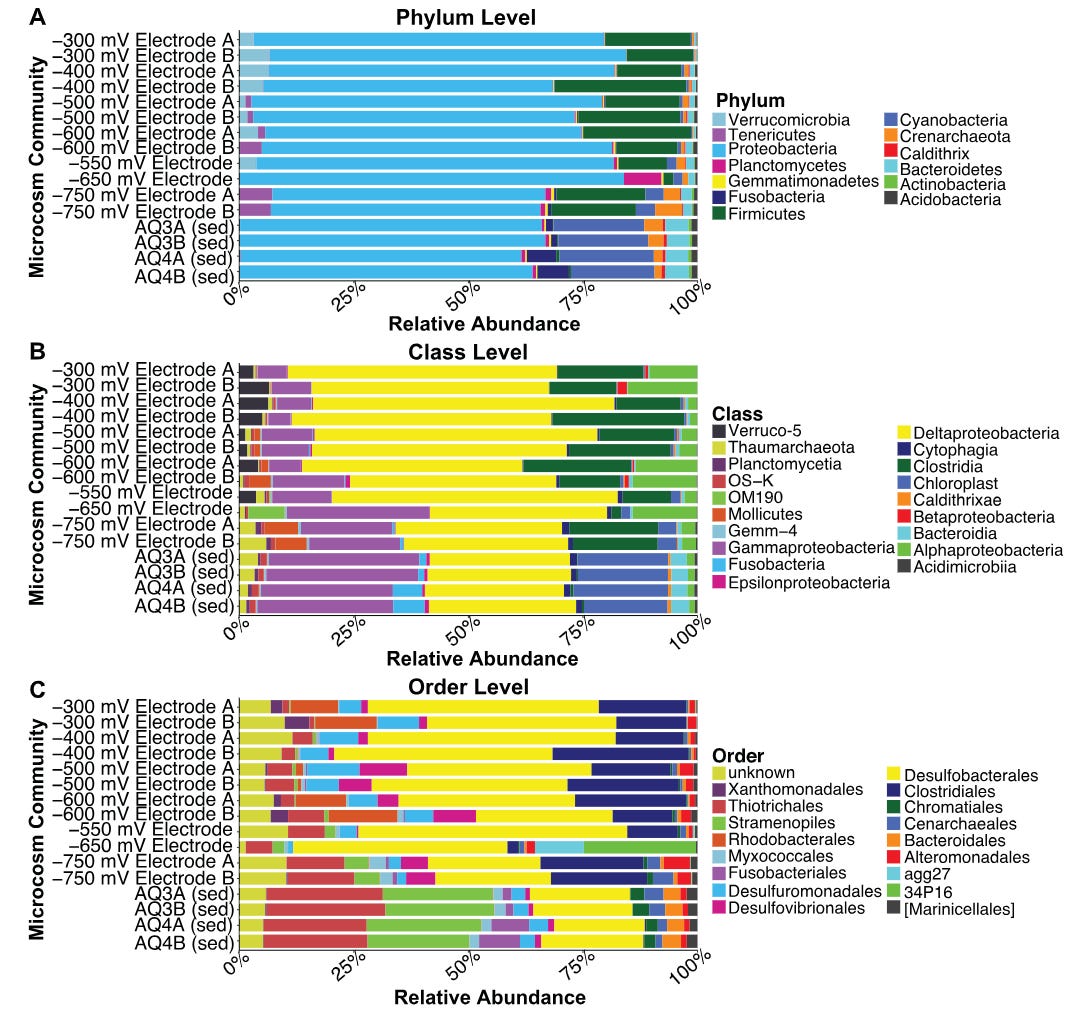

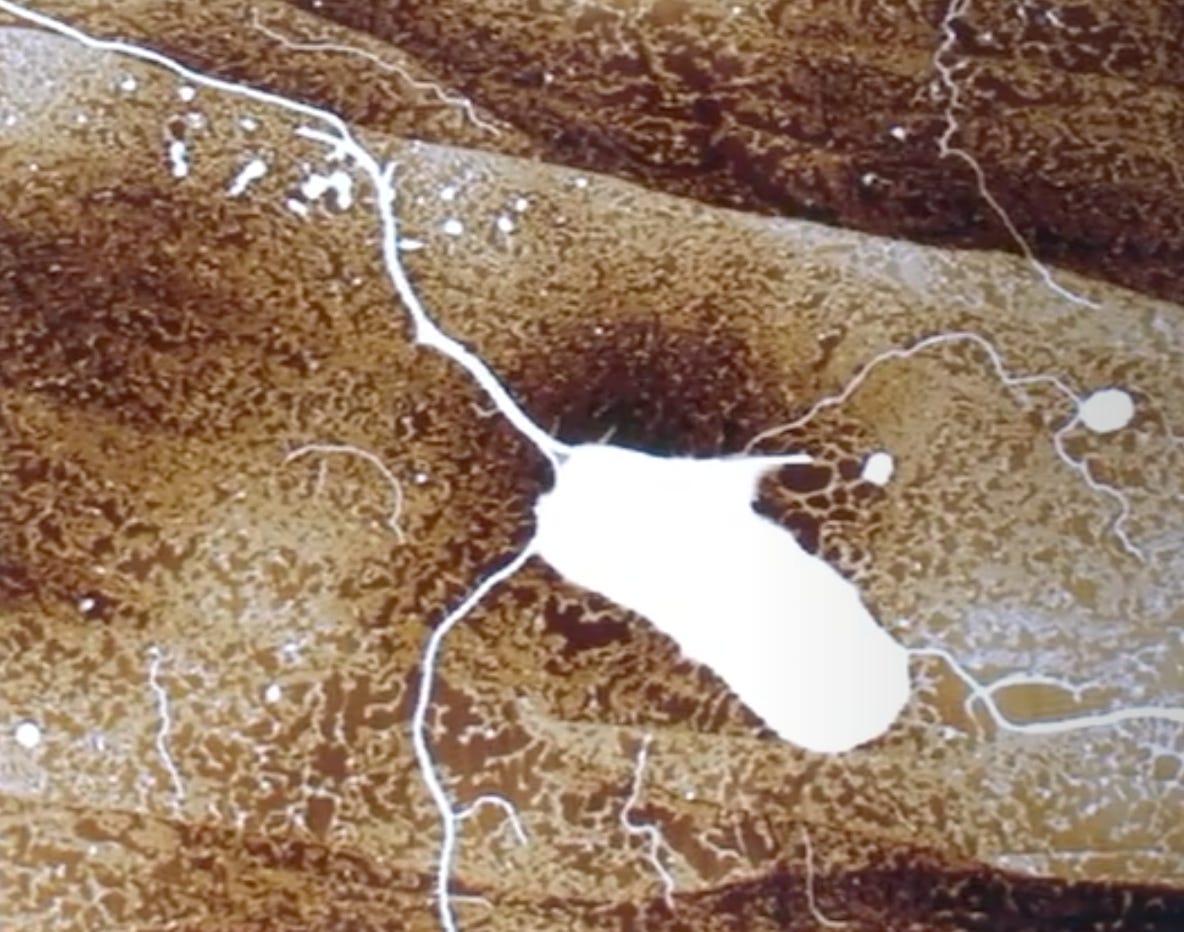

What this phenomena explicitly highlights is the how bioelectrical symbioses can shape entire microbial communities. The need for both labile electrons to run the transformative capacity of energy metabolism and for a terminal electron acceptor to complete the loop generates natural communities that depend on their local electrical environment.5 Bacteria that reduce their environment couple with those that oxidise it, such that different species can become mutually dependent on each other. This establishes complex bacterial communities that can be shaped by electricity rather than a carbon/food source. Even shifts on the order of 3mV can produce significant shifts in the microbial composition of these EET-using cultures.6

What is most fascinating about this pertains to the energetic nature of bacteria and the implications this holds for understanding their symbiotic relationship with us. Our microbiomes do not shift based solely on our diet, rather, they are shaped directly by the energetic environment in which they live.7 This insight into the complexities of bacterial energy metabolism could allow us to further understand why exercise, light exposure, psychological state, sleep quality and respiration can all shape our microbiome. Bacteria employ unique methods of energy transformation, some of which only make sense within the context of certain ecologies, where symbioses exist. In other words, metabolic diversity parallels community composition.

“When it was discovered that bacteria could be maintained on the cathode, using electricity as their source of energy, the field of electrobiosynthesis was born”

— Nealson, 2017

While these studies examined marine sediment bacteria, not commensal bacteria found in the human gut, in personal communications with Ken Nealson, he said that he suspects similar phenomenon are likely taking place in biological systems. Although this is tentative as these phenomena are yet to be explored regarding biological systems, the human body is a perfect candidate to foster these types of electrical relationships between microbes.8 With this in mind, it should also be noted that a significant proportion of human gastrointestinal bacteria cannot yet be studied outside the body, leaving a significant potential for this type of phenomena to occur.

“YES I would expect that microbiomes of many organisms would be great places for electrical interactions between microbes and their hosts.”

— Kenneth Nealson, personal communication.

I hope to highlight how the composition of microbiomes can be shaped by their energetic environment — not just by the specific carbon/food source they are supplied with. These studies on electrobiosynthesis make salient how small energetic changes to the culture’s environment can lead to significant changes to the bacterial diversity and composition. As energy flows throughout the body, it seems naïve to dismiss the possibility that these fluxes do not regulate the populations of our commensal bacteria. This is likely one of the reasons why microbial populations shift in a circadian fashion as energy transformation ebbs and flows throughout the day9, or why exercise can either benefit or damage the gut microbiome depending on intensity10. With a primary energetic input being sunlight, it becomes obvious how sun exposure modulates all of our microbiomes, not just our gut.11

In light of this, it may become clearer why probiotics and prebiotics are such a hit-and-miss approach to gut-related issues, and even if benefits result, they are often transient. What is more fundamental to a microbiome’s health is the energetic environment. This concept is even reflected in the four D’s of niacin (vitamin B3) deficiency, one of them being diarrhoea; without the ability to transform and utilise energy (NAD+, the principal electron donor in the ETC is built on niacin), the gut lining and associated bacteria cannot function properly. In a similar manner, pesticides like glyphosate interfere with the bioenergetics of the body in various ways, shaping the microbiome both directly and indirectly.

What I hope to convey is that our resident microbial populations are not modulated solely by their food source. Our microbiomes are a result of the integrated energetic signals we receive from our environment. From light, to exercise, to psychological state12, each unique way in which our energy flow is shifted is likely to shape the composition of our various microbiomes. Gut problems have become so common that they are becoming normalised. While the solutions in most practitioner’s eyes revolve around supplements, diet and probiotics, a central focus must be the flow of energy. With the primary dictators of optimal energy transformation being sunlight, strong circadian rhythm, good sleep, positive affect, locale-specific diet and limiting hyper-novel stimuli including synthetic chemicals, microplastics and non-native EMF, it seems logical to begin with these modalities first when addressing gut-related issues.

Summary

Specific bacteria have been found that are capable of extracellular electron transport (EET), where their acquisition and depositing of electrons used in their energy metabolism are external.

Communities of diverse EET-utilising bacteria can be modulated by their culturing on electrodes at varying electrical conditions. Even changes on the order of <10mV can produce significant changes in the bacterial communities. These shifts are explained by the coupling of diverse metabolic strategies between bacterial species — ie., some bacteria respire their ‘waste’ electrons to a bacterial that acquires it to run its energy metabolism. Small shifts in the supply of electrons from the anode can scale up to large shifts at the level of the entire population.

While these EET-using bacteria are from marine sediments, it highlights the metabolic diversity of microbial populations and how they are sensitive to their local energetic environment.

These studies may help us understand why stimuli that alter the energetic flow of the body also shape our microbial populations. It may be that similar energy-related influences on microbial metabolisms impact the composition and diversity of our symbiotic microbes. This could help to explain the various findings of how exercise, sleep, circadian rhythm, light exposure and psychological states all impact our microbiomes.

Related Articles

Related Podcasts

See more here: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/microbes-breathe-and-eat-electricity-make-us-re-think-what-life-180953883/

M. C. Potter, (1911), Electrical effects accompanying the decomposition of organic compounds, Proc Biol Sci, 84 (571): 260–276 .

Rowe, A. R., Chellamuthu, P., Lam, B., Okamoto, A., & Nealson, K. H. (2015). Marine sediments microbes capable of electrode oxidation as a surrogate for lithotrophic insoluble substrate metabolism. Frontiers in microbiology, 5, 784.

Lam, B. R., Barr, C. R., Rowe, A. R., & Nealson, K. H. (2019). Differences in Applied Redox Potential on Cathodes Enrich for Diverse Electrochemically Active Microbial Isolates From a Marine Sediment. Frontiers in microbiology, 10, 1979.

Lam, B. R., Rowe, A. R., & Nealson, K. H. (2018). Variation in electrode redox potential selects for different microorganisms under cathodic current flow from electrodes in marine sediments. Environmental microbiology, 20(6), 2270–2287.

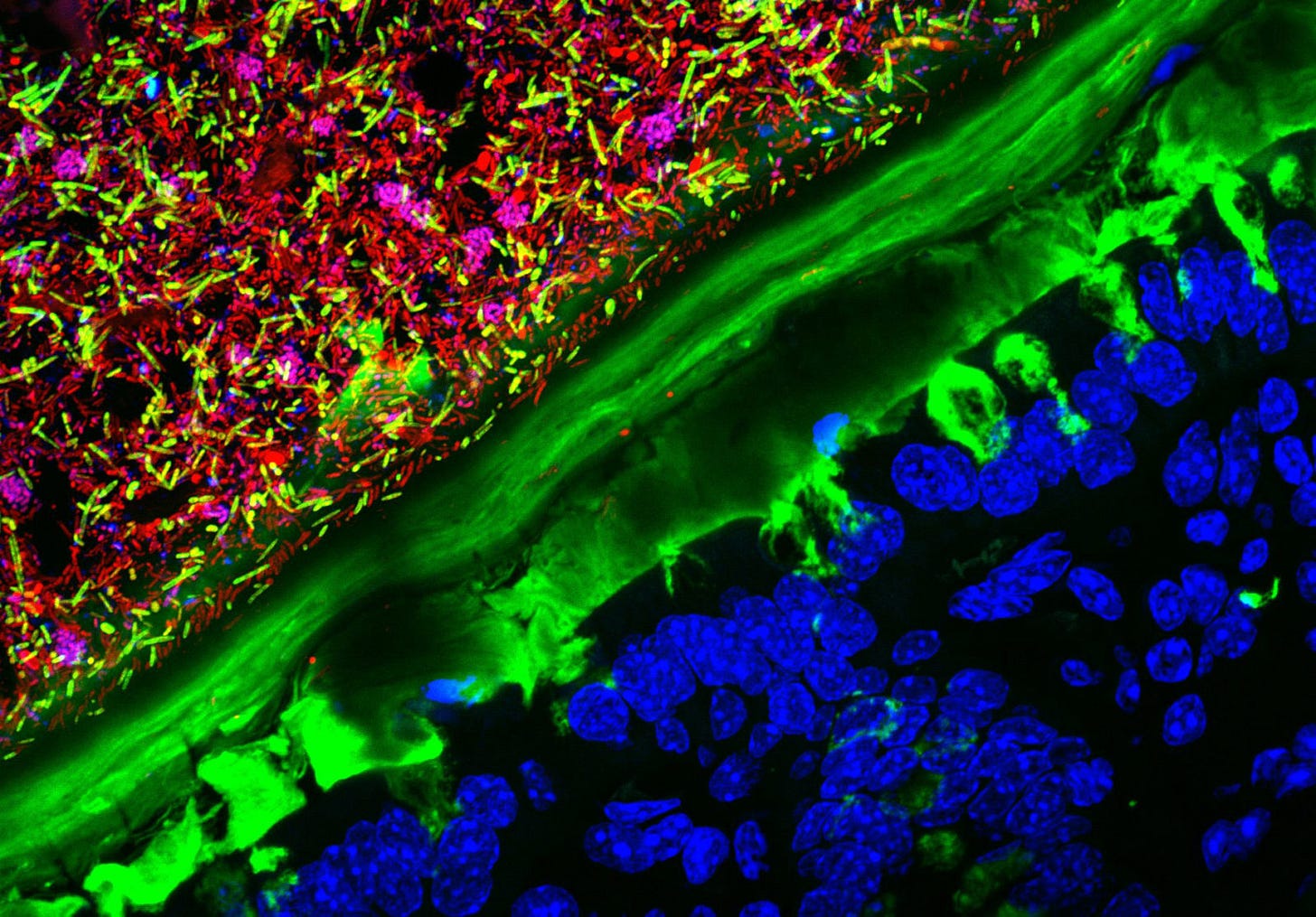

Parallel to this notion is the bacterial production of biofilms — a critical aspect of these types of bacteria. Biofilms play an important role in the gut, pointing to a tenuous, yet fascinating idea that our bioenergetic state can modulate biofilm production.

While this is not directly published in the Lam paper, Nick Lane discusses the sensitivity to changes of this magnitude here.

Some of which is determined by the foods we eat and ultimately the food sources our commensal bacteria receive.

There is evidence that modalities like photobiomodulation, a potent vector for bioenrgetic change, influences the gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease patients. See more here: Bicknell, B., Liebert, A., McLachlan, C. S., & Kiat, H. (2022). Microbiome Changes in Humans with Parkinson's Disease after Photobiomodulation Therapy: A Retrospective Study. Journal of personalized medicine, 12(1), 49.

Takayasu, L., Suda, W., Takanashi, K., Iioka, E., Kurokawa, R., Shindo, C., et al. (2017). Circadian oscillations of microbial and functional composition in the human salivary microbiome. DNA research : an international journal for rapid publication of reports on genes and genomes, 24(3), 261–270.

Dziewiecka, H., Buttar, H. S., Kasperska, A., Ostapiuk-Karolczuk, J., Domagalska, M., Cichoń, J., & Skarpańska-Stejnborn, A. (2022). Physical activity induced alterations of gut microbiota in humans: a systematic review. BMC sports science, medicine & rehabilitation, 14(1), 122.

Of course, the bioenergetic impact on microbial populations is not restricted to the gut microbiome, but extends to the skin, eyes, lungs, genitals etc.

Conteville, L. C., & Vicente, A. C. P. (2020). Skin exposure to sunlight: a factor modulating the human gut microbiome composition. Gut microbes, 11(5), 1135–1138.

Harel, N., Ogen-Shtern, N., Reshef, L., Biran, D., Ron, E. Z., & Gophna, U. (2023). Skin microbiome bacteria enriched following long sun exposure can reduce oxidative damage. Research in microbiology, 174(8), 104138.

Ma, L., Yan, Y., Webb, R. J., Li, Y., Mehrabani, S., Xin, B., Sun, X., Wang, Y., & Mazidi, M. (2023). Psychological Stress and Gut Microbiota Composition: A Systematic Review of Human Studies. Neuropsychobiology, 82(5), 247–262.