Between the 16th and 18th centuries, the often fatal disease known as scurvy ravaged many sailors and their crews. Isolated at sea for sometimes months at a time, there was essentially no capacity to store fresh produce for those onboard. Surviving on staples such as bread, ships biscuits, salted meats, cheeses and fish (all foods essentially devoid of the then unknown, vitamin C), symptoms of disease including loss of teeth, delirium, dysautonomia (and ultimately death) would take hold, resulting in devastating effects on international trading and commerce.

Without knowing why, consumption of citrus fruits, particularly lemons and limes, appeared to have a salutary effect on limiting the incidence of scurvy on ships.1 Eventually, carrying citrus on voyages became a mainstay and scurvy was largely eliminated.

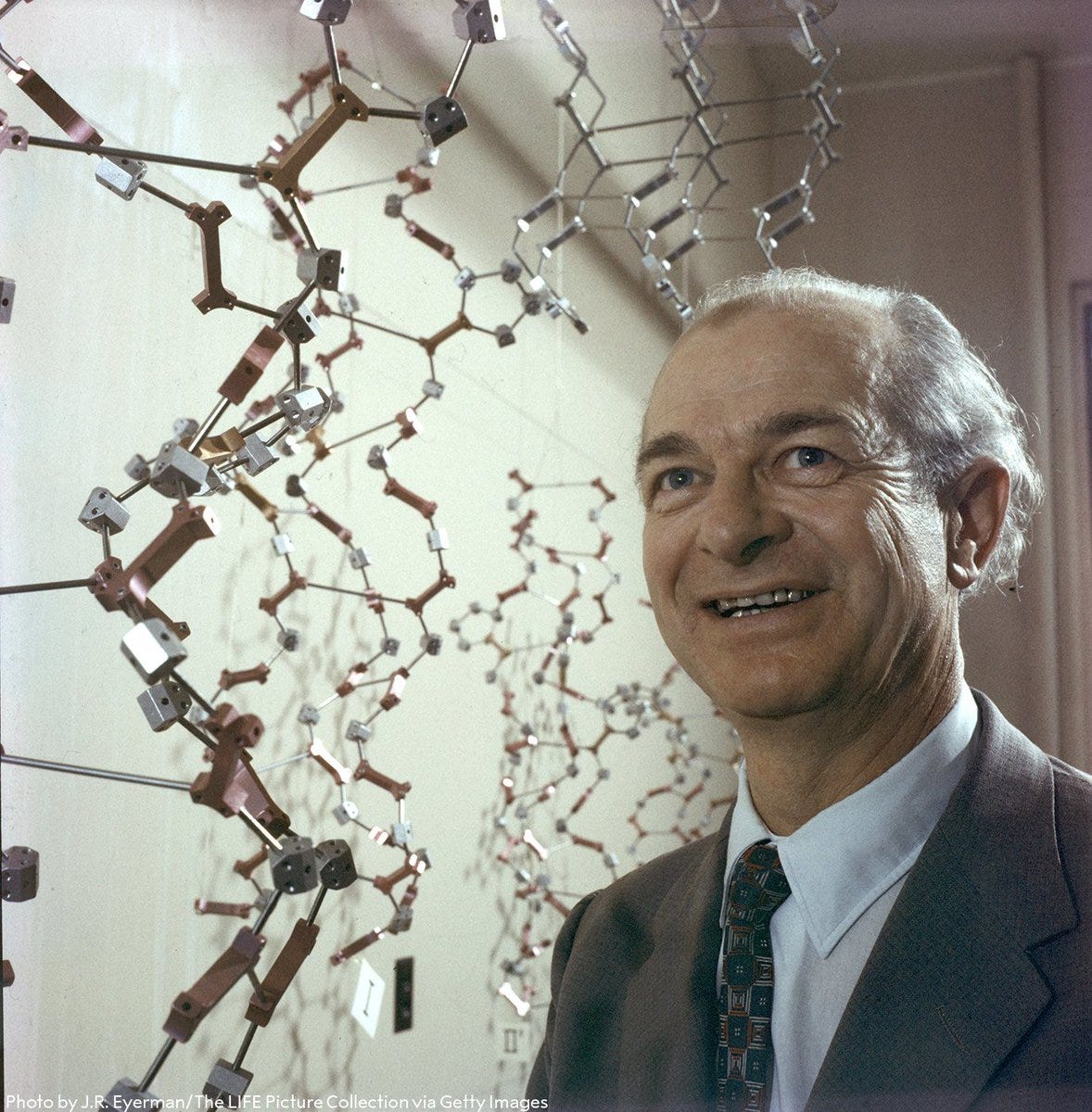

It wasn’t until 1970 when famous Nobel Lauriat, Linus Pauling discovered the famed nutrient, Vitamin C. Much fanfare was made about its potential use in health and disease, and its importance in human physiology is still echoed in the marketing of vitamin C supplements today. A vitamin is, by definition, essential to human function (without consumption, we will die) and not made endogenously.2 Without the ability to make it endogenously like other mammalian species, our bodies expects intake of a certain amount on a somewhat regular basis.

Fast forward to the early 2010s and the murmurs of carnivorous diets are increasing in volume. Proponents including Shawn Baker and Paul Saladino shook up the already confusing (and at times, toxic) diet culture with their meat-only diets.

The seeming long-term (apparent) success of their diets begged questions from many: “But wait, shouldn’t these carnivores be succumbing to scurvy? How are all of these people not consuming any vitamin C but not getting scurvy even though we know that’s what happens? If they can survive without any vitamin C, is it really even technically a vitamin at all?”

As it turns out, “requirements”3 for vitamin C do not appear to be fixed. The necessary intake of vitamin C for normal physiological function appears to be contingent on other related factors; dietary and environmental. This was well understood many decades ago but largely forgotten in the nutrition world.

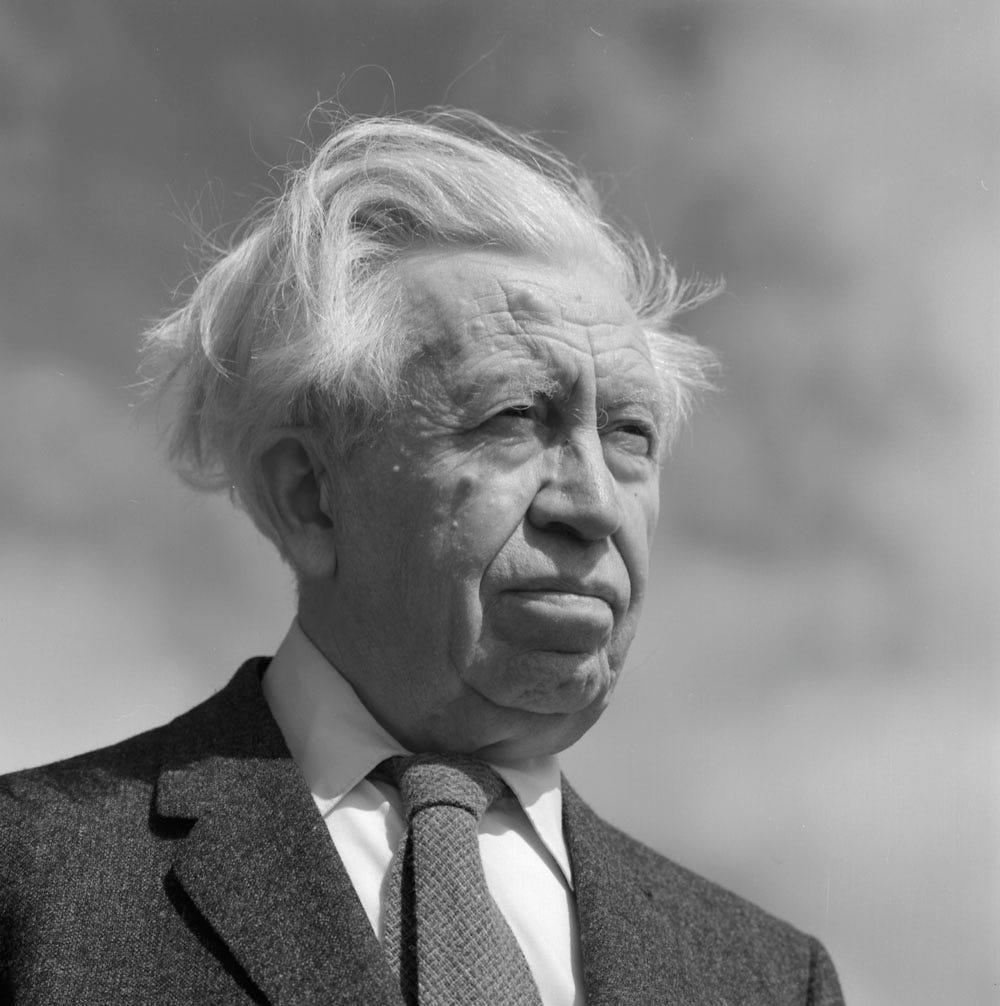

In the early part of the 20th century, arctic explorer and ethnologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson had made expeditions wherein he met peoples who had survived almost exclusively on diets of animal flesh. Documented in his 1956 book, “The Fat of The Land”, Stefansson noted that he himself could live perfectly healthily on a diet of meat only; just as the indigenous cultures in the arctic had for generations. As vitamin C was still to be discovered, questions surrounding deficiency were simply not asked. Again, the fresh (and at times, raw meat), likely provided trace amounts of vitamin C capable of preventing the cardinal signs of scurvy, but it also appeared that in the presence of a diet rich in fat and protein, less vitamin C was required.

One of the first signs of this was that in the absence of carbohydrate consumption, vitamin C requirements appear to drop proportionally. So much so that those abstaining from any plant material at all could be sustained on the miniscule amounts of vitamin C present (<10mg/day) in any rare or raw meat they were consuming.4 This appears to be why a diet consisting only of meat may not cause scurvy, but a diet rich in carbohydrate can.

Herein lies the workings of a system I refer to as ‘Biochemical Tensegrity’.